by Christopher Witmore

When presented with the question of

“why I became an archaeologist” I tend to cycle between 3 different

responses; responses all rooted in childhood experiences. Indeed, which

of these I dispense varies with whom I am speaking. My answers are:

1) I enjoyed both digging up and collecting bits and pieces of glass and metal on the family farm as a kid.

2) From age 10, when my mother purchased the subscription, I regularly

read about archaeology in National Geographic (this routine was tempered

by my love of fantasy world literatures).

3) Indiana Jones was one of my childhood heroes.

Now it should go without saying that none of these responses, when

taken on their own, even comes near to accounting for why I was drawn

down the long path (the length of which, of course, varies) to becoming

an archaeologist. Far beyond what may have been my other, and diverse,

childhood influences — films from Spartacus and Clash of the Titans to

Excalibur and Conan, a passing obsession with Dungeons and Dragons,

authors of fiction like J.R.R. Tolkien or C.S. Lewis (Michael Shanks

once told me that almost half of the undergraduates at the University of

Wales Lampeter were drawn to archaeology because of the allure of the

fantastical realms created by Tolkien and Lewis), and, of course, the

associated backyard battles with my brothers clad in armor fashioned

from scraps of plywood, tin roofing and duck tape — one has to account

for the wider web of other influences, no matter how standout or subtle,

that impacted their formation along the circuitous course to an

advanced academic degree in archaeology and beyond. The distance between

now and then is tremendous. Still, childhood fascinations count for a

great deal — the past was a place of wonderment and imagination.

In retrospect, and given my rural roots in the North American

Southeast, the portrayal of the past (whether fact or fiction) and

archaeology on television, in magazines and novels had a profound

impact. And yet, surprisingly few have chosen to take these fields of

cultural production seriously (Finn 2004; Holtorf 2004 and 2007; Lucas

2004; Pearson and Shanks 2001; Shanks 1992; also refer to

Michael Shanks on the archaeological imagination).

In his latest book,

Archaeology is a Brand!, Cornelius

Holtorf asks his readers to hold the almost obligatory negative

responses so often tempered with ridicule and scorn by academic

archaeologists and to consider the topic of “archaeology in popular

culture” with an ‘open mind’ (also see Holtorf 2008). In this, he is

neither concerned with past-as-play videogames like

Praetorians,

the fascination with the fantasy worlds of Avalon and Middle Earth,

movies such as Alexander (Cherry 2009(in press)), nor the jousting

competition at

King Richard’s 16th-century faire.

Quite specifically, the book addresses the “meaning” of archaeology as

generated in television, movies, literature (both fictional and

nonfictional), newspapers, or even

National Geographic; all mass media which Holtorf takes to be “popular culture” (though he prefers the term

Alltagskultur

or “everyday culture” as enrolled by German folklorists (2004, 7-12)).

The argument, echoing the sentiments of Gavin Lucas, is that the major

allure of archaeology lies more in popular culture than in “any noble

vision of improving self –awareness through “historical perspectives””

(Holtorf 2004, 3 after Lucas 2004, 119). Moreover, this fascination, for

Holtorf is “rooted in a few key stereotypes and clichés” (2004, 130):

1) the archaeologist as adventurer (also refer to Holtorf's recent

Archaeolog entry:

Hero! Real archaeology and ”Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull”);

2) the archaeologist as detective; 3) the archaeologist as infallible

producer of “profound revelations;” and 4) the archaeologist as heritage

steward.

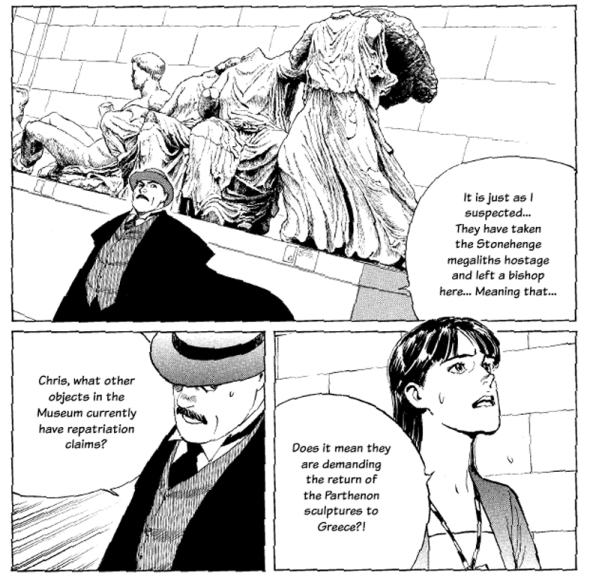

Light-hearted and somewhat relaxed,

Holtorf’s style is buttressed by the mildly humorous cartoon

illustrations of Quentin Drew. These illustrations parody many

situations associated with the aforementioned stereotypes.

For example, the caption for the image included here reads:

“Professor, you stand accused of elitism and a disregard of popular

community interests. How do you plead?” We might hasten to add other

adjectives to describe these images and yet, however readers view the

cartoons, the almost exclusive use of this imagery reiterates the point:

loosen up and enjoy the past. And if this

message doesn’t ring loud and clear through the work of the

illustrations, then perhaps with the aid of the kineographs (flipbook

images) at the bottom corner of every page it will.

The TV series Time Team and the work of Gisela Graichen, headlines in

Leipziger Volkszeitung (www.lvz-online.de) and the Boston Globe,

Holtorf argues the draw of archaeology in such mass media pertains more

to the celebration of archaeological work than to any educational value

generated with regard to long gone pasts (2007, 50). Given this

emphasis, archaeology enjoys an extremely positive image in ‘the public

domain.’ The discipline has what Holtorf calls “archaeo-appeal.” As

such, archaeology is a ‘successful brand’ and archaeologists are

encouraged to make the most of this. To what ends, I will raise shortly.

In Archaeology is a Brand! Holtorf asks some awkward

questions about the value of archaeology’s past production, academic

authority, and ‘social’ role. These questions are critical for goading

archaeologists to consider the powers of their work in light of the

contemporary climes we find ourselves in. I too am provoked. The reason

for this is not due to the potentially unsettling arguments present in

the book (v); indeed, anyone who has read his work before is familiar

with such colorful mainstays of Holtorf’s articles and books more

generally. To the contrary, I am provoked because of the book’s failure

to deliver on what is arguably its core proposition. Because this defect

detracts significantly from an otherwise important arena in need of

more scholarly attention I will dedicate most of this entry to the close

scrutiny of it.

To underline the core proposition, archaeologists need to understand

the desires of their mass audience because archaeology is ultimately in

service of society. If we are to understand our mass audience and their

desires, we need to come to terms with how our craft is portrayed in

‘popular culture;’ a popular culture associated with a leisure economy.

This is an admirable and legitimate goal. However, the path to attaining

it is set upon shaky ground beginning with the circumscribed rendering

of both ‘popular culture’ and ‘society.’

Readers are given little to work with regarding the term ‘popular culture’ in

Archaeology is a Brand!

— Holtorf works with no ‘rigid definition.’ So to get a better sense

of how he deploys the term we have to begin elsewhere. Somewhere between

Stonehenge and Las Vegas,

Holtorf states: “popular culture refers to how people choose to live

their own lives, how they perceive and shape their local environments

through their actions, and what they find appealing or interesting”

(2004: 8). Popular culture “expresses—and reproduces—our inner thoughts

and emotions, our (supposedly) secret fears and desires, and our

favorite habits and behaviors” (Ibid.). So here, while Holtorf

recognizes the diverse resonances associated with such a diffuse term

(amplified by being crafted out of two of the most disputed notions in

academic history: ‘popular’ and ‘culture’ (see for example Fiske 1989;

Jenks 2003; Kroeber and Kluckhohm 1952)), he nonetheless identifies

popular culture with personal as well as group preferences and the

articulation of our ‘inner’ emotions and thoughts. Importantly, Holtorf

places emphasis on how the notion is more about actively creating

‘culture’ rather than passively receiving it.

Likewise, in

Archaeology is a Brand ‘popular culture’ is

linked largely to TV programs and newspapers and according to Holtorf,

these “to a greater extent than any other media . . . are both

influencing and reflecting what people know and how they think” (2007,

29). And yet, elsewhere we are told “popular culture is however not

identical with people’s perceptions of beliefs” (51) in the context of

distancing the concerns of archaeology’s audience from the ‘popular

culture’ they consume. Such concerns seem incongruous. On the one hand,

popular culture is about what people find appealing or interesting,

about what they express and create. On the other hand, it really doesn’t

matter what people think as Holtorf “is not concerned with gauging

public support for archaeology or preservation, evaluating the accuracy

of popular beliefs about archaeology or heritage, or establishing basic

demographic facts about visitors and their knowledge” (60-61). In one

section ‘society’s’ perceptions count for everything, in another they

are irrelevant (unless we are to imagine a society composed only of the

few archaeologists, producers and journalists directly involved in the

generation of the mass media Holtorf deals with). Here, Holtorf explains

away what should have formed a significant portion of the study and it

is here that we fall into a rather large hole in the book; a hole so

large that it swallows up any space I might have reserved for a

discussion of the book’s merits (click here for the e-book version of

the contents:

http://traumwerk.stanford.edu:3455/PopularArchaeology/Home).

In fact, this hole is centered upon Chapter 4, “What people are

thinking about archaeology.” The shortest chapter in the book, this

chapter actually tells readers very little about ‘what people are

thinking’ (Holtorf admits he would have loved to have found out more

about what how people ‘perceived’ archaeologists and archaeology but he

was unsuccessful with obtaining the necessary funding). Instead, the

chapter is a synthesis of other published surveys, surveys conducted to

different ends, which tell us that the single most important source of

information about archaeology is TV (51-54). The Internet figures very

little in these surveys and this renders portions of the study, if not

out-of-date, incongruent with our times (refer to

Archaeology: A stratigraphic profile by Google).

Ultimately, for Holtorf, “the most important question that

archaeologists in public contexts need to ask their audiences is not

“How can I best persuade you about the merits of my project or

discipline?” but “What does what I am doing mean to you?” (2007, 139).

Should you choose to search for the answer to this very question, you

will not find it in the book.

How are we to understand the society we are in service of? How do we

gauge peoples’ desires in relation to the portrayals of archaeology in

mass media? Could I say that a landowner’s anger and frustration with

archaeologists of the local service in Nafplion, Greece for barring him

from building an addition on his house in the A zone of an

archaeological site is offset by the positive image of the adventurer

Indiana Jones playing in the former Mosque-turned-cinema across the

square from the very offices of the archaeological service he spent

several hours in that morning? Yes? No? Maybe? In all likelihood, I can

say that whatever meanings associated with archaeology that were

‘reflected’ in and ‘derived’ from popular culture have been modified by

an exchange with what he has come to regard as a rather ‘un-popular

culture.’ Of course, no one could be sure one way or the other without

putting in the many painstaking hours necessary for tracking down the

heterogeneous relations which give rise to one’s idiosyncratic, even

conflicting associations, desires, emotions, meanings, whatever.

For Holtorf, archaeologists have a professional duty to fulfill “a

social role that is widely appreciated in society” (141). But of what

society does he speak? What public? Developers in East Crete? Tourists

at Stonehenge? Asparagus farmers in Braunschweig? Toltec shamans at

Teotihuacán? I am sure they all have different appreciations — even in

relation to fellow group members — and one cannot say for sure how

‘popular culture’ figures into the meaning they associate with

archaeology. One cannot even say in advance whether ‘popular culture’

speaks for, reflects, arises out of, or enacts popular sentiment. We

cannot say in advance because these very relationships are what need to

be established on the ground. The almost-complete lack of any attempt to

hit the pavement with the actual people who populate this so-called

public in specific locales betrays the limited scope which Holtorf

grants to the ‘society’ archaeologists are supposed to be in service of.

To be fair, 5 days of a fact-finding mission to the UK translated into

the narrative of a travelogue in Chapter 1 is a start. Here, while

Holtorf engages issues of where people along his path come into contact

with archaeology on a daily basis, he only speaks with professional

archaeologists and heritage workers. Aside from this, the study does not

benefit from the rewards of an anthropological approach; an approach

which Holtorf claimed to have employed when forced to assert his

academic authority (Holtorf 2008); an approach which Holtorf is quite

clearly adept at deploying (2002). We might compare, for example,

Barbara Bender’s efforts to document contemporary relations with

Stonehenge (1998) or Timothy Webmoor’s study of resident, employee and

visitor relations at Teotihuacán based on dozens of interviews and 471

seven-page questionnaires (2007). Holtorf has not put in the many hours

of meticulous research that are necessary to flush out the web of

connections between mass media and the masses it purports to represent.

Never mind the lessons of critical theory (Adorno 1991; Leone, Potter

and Shackel 1987; Shanks and Tilley 1992).

In the end, Holtorf cannot argue for ‘people’ in society; he cannot

suggest we practitioners question the audience of archaeology as

portrayed in popular culture; he cannot do so because he has not engaged

them. For Holtorf to argue on behalf of 'society' without conspiring

with all of its diverse constituents is itself a form of

misrepresentation. Unfortunately, readers are left with missing masses.

Without the substantive research deployed to add weight to the core

thesis, readers are presented with a study that comes up short. Holtorf

doesn’t practice what he preaches and Archaeology is a Brand doesn’t make the point it purports to make; it does not deliver on what is arguably its core message — know the desires of ‘society.’

Where the book does succeed is in amplifying archaeology’s narcissism

by telling us — as members of this 'popular culture' — what we already

knew. What it does deliver is a different message: archaeology needs to

be in service of mass media — as popular culture is conflated with mass

media (movies, TV programs, advertising, toys, fictional and

non-fictional literature, museums, etc.) and society’s appreciation is

conflated with what is ‘reflected’ in that mass media (also refer to

Kristiansen 2008). To get at the resources necessary for understanding

what society appreciates about archaeology we need not leave the

comforts of our very own couch!

Shall we (de)limit the archaeological imagination on the basis of

public opinion mass media? I hope not. Of course, I don’t think Holtorf

would claim this outright, but the composition of the study, I suggest,

does his agenda a major disservice.

I will conclude with a few more observations.

Holtorf suggests archaeology may have little more to offer society

than temporary escapes from the ‘real’ world (145). Again, we must take

this as an incitement to contemplate other archaeological benefits for

‘society’ and that includes not only reconsidering the composition of

society but also the relations between past and present. As Holtorf

perhaps less than amicably suggests, we need not only consider questions

of the past in the past (the ‘past as it was’ is always the outcome of

our practices) but also how the past is mixed up in the polychonic

ensemble of the present. In this, ‘popular culture’ is perhaps only a

subset of the bewildering varieties of relations out there. Nonetheless,

archaeology must do a better job of demonstrating why the things ‘of

the past’ are much more interesting and lively than any of our

representations, popular or professional, have allowed (Gonzalez-Ruibal

2008).

It is unfortunate that this commentary has taken on too many

characteristics of a diatribe. It is unfortunate because Holtorf and I

share a number of common concerns. I too believe it is time to reassess

some of archaeology’s core ingredients from the ground up. I too hold

that we need to readdress questions of direction and purpose. There are

many others who also hold these concerns, to be sure. It is because of

this that I plead for more careful and substantive labor in backing up

such challenging propositions. We have to do a better job of supporting

our arguments through richer empirical accounts. If we choose the paths

of least resistance, if we take shortcuts, then such otherwise bold work

will be full of defects, defects for which consumers in the leisure

economy have the right to demand the implementation of quality controls

and to recommend a recall by the publisher/producers of such work.

References

Adorno, T.W. 1991: The Culture Industry: Selected Essays on Mass Culture. London: Routledge.

Bender, B. 1998: Stonehenge: Making Space. Oxford: Berg.

Cherry, J.F. 2009(in press) ‘Blockbuster! Museum Responses to Alexander the Great’ in P. Cartledge and F. Greenland (eds.), Responses to Alexander: Film, History and Culture Studies after Oliver Stone's 'Alexander'. University of Wisconsin Press. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

Finn, C. 2004: Past Poetic: Archaeology and the Poetry of W.B. Yeats and Seamus Heaney. Duckworth Publishers.

Fiske, J. 1989: Understanding Popular Culture. London: Routledge.

González-Ruibal, A. 2008: Time to destroy: An archaeology of supermodernity. Current Anthropology 49(2), 247-79.

Holtorf, C. 2002. Notes on the life history of a pot shard. Journal of Material Culture 7 (1): 49–71.

Holtorf, C. 2005: From Stonehenge to Las Vegas. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

Holtorf, C. 2007: Archaeology is a Brand! Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

Holtorf, C. 2008: Academic critique and a need for an open mind (a response to Kristiansen) Antiquity 82, 490-92.

Jenks, C. 2002: Culture: Critical Concepts in Sociology. London: Routledge.

Kristiansen, K. 2008: Sould archaeology be in service of ‘popular

culture’? A theoretical and political critique of Cornelius Holtorf’s

vision of archaeology. Antiquity 82, 488-92.

Leone, M., P.B. Potter, and P.A. Shackel, 1987. Towards a Critical Archaeology. Current Anthropology 28(3), 283-302.

Lucas, G. 2004: Modern Disturbances: On the Ambiguities of Archaeology. Modernism/Modernity. 11(1), 109-120.

Kroeber, A.L. and C. Kluckhohm, 1952: Culture: A Critical Review of Concepts and Definitions. Harvard University Peabody Museum of American Archeology and Ethnology Papers 47.

Pearson, M. and M. Shanks, 2001: Theatre/Archaeology. New York: Routledge.

Shanks, M. and C. Tilley, 1992. Reconstructing Archaeology. London: Routledge.

Webmoor, T. 2007: Reconfiguring the Archaeological Sensibility: mediating heritage at Teotihuacan, Mexico. Doctoral dissertation. Department of Anthropology, Stanford University.